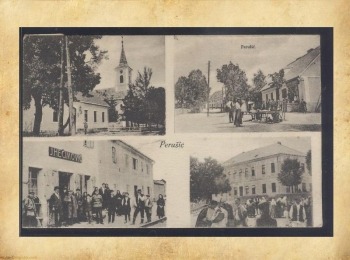

Perušić - place of turbulent history

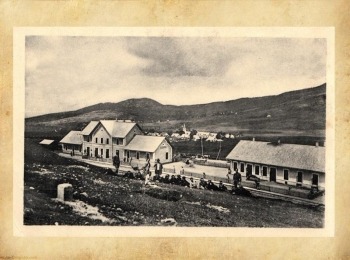

A turbulent and rich history marked Perušić. Since prehistoric times, the area has been suitable for habitation due to its vegetation, accessible hills, and proximity to water sources. The roads that connected the west and the east, the mainland and the coast often crossed the area of the modern-day Perušić, and all of the above has influenced the human presence since ancient times. Numerous caves that can be found in this area served as a shelter for anyone who stumbled upon them. However, we have been seeing specific traces of life since the 9th century BC, when Iapodes appear in that area, as evidenced by two localities, Mali Čardak and Lipova Glavica. In the 1st century BC, the Romans arrive, they wage and win the war against the Iapods, and in the end only the Romanized Iapods remain. Throughout the Middle Ages, Perušić was mentioned under the name of Buška Vrhovina, part of the Bužani parish mentioned by the Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus in the work “On the Management of the Empire”. Shortly afterwards, the Frankopans appeared and built a fortified castle as early as in the 11th century. It is precisely this castle that will later become the most famous symbol of this place, which will come into the possession of the Perušić family, the first rulers of the town of Perušić, thanks to a donation from the Brinje prince Anž Frankopan. Then comes the turbulent period in which the Ottoman army conquered the area and ruled the town for 160 years until 1696 when the Turkish army left the fort and the population that remained in their homes was baptized by the priest Marko Mesić. The town then became part of the Military Frontier in 1712 until its dissolution in the second half of the 19th century when it became part of Banska Hrvatska. In the census conducted in 1876, Perušić had 600 inhabitants, and a post office was opened the same year. The girls’ school was opened in 1874, and in 1910, the Perušić district had 21,000 inhabitants, and a railway station was opened ten years later. Since then, the population has been gradually declining primarily due to wars, and today that number does not exceed 1,500.

CHURCH OF THE EXALTATION OF THE HOLY CROSS

Following the liberation of Lika, priest Marko Mesić founded a parish in Perušić as early as in 1680. According to Horvat, it seems that a wooden church was built first, although there was a Gothic church that was converted into a mosque during the Ottoman rule. In a record from 1768, archdeacon Kabalin states that the church in Perušić does not have a floor, and that the ceiling has not been completed. It is the largest sacral building in Lika – it is 34 meters long and 13.85 meters wide, and it consists of a spacious nave with eight chapels arranged in equal numbers on each side of the nave, a short polygonal sanctuary, a sacristy located on the southern part of the sanctuary, and a bell tower located in front of the main facade. Above the side chapels there are the emporiums (architecturally elevated space inside the church) with their own windows. Above the nave there is a flat ceiling, as well as above the sanctuary, and they are the same height. In the southern part of the sacristy there is a spolium (built-in remains of an earlier structure used as building material for a new one), which serves as proof of the existence of an older structure on the site.

The bell tower of the church has late Gothic features, such as a pointed-arch Gothic portal and small windows to illuminate the interior, some of which are also pointed. The ground floor of the bell tower is vaulted with a semicircular barrel vault. As far as the layout, the measurements of the bell tower are 419/405 centimeters, and it fits into a series of medieval bell towers of the Lika country churches (Horvat 2003: 138-139). The very portal of the church has a pronounced Gothic profile, as does the Gothic church of the Holy Trinity located in Podovi, near Perušić. Above the entrance portal is a lunette with the year 1698 and the Latin inscription “In hoc signo vinces, hic opvs meae salvtis” (In this sign thou shalt conquer). The lunette itself is not Romanesque, but it is evident that it was carved after the liberation of Lika from the Turks, which also means that the said year was not added, but the lunette and the inscription were created in the same period (Horvat 2003: 140).